Review of Down Home Music

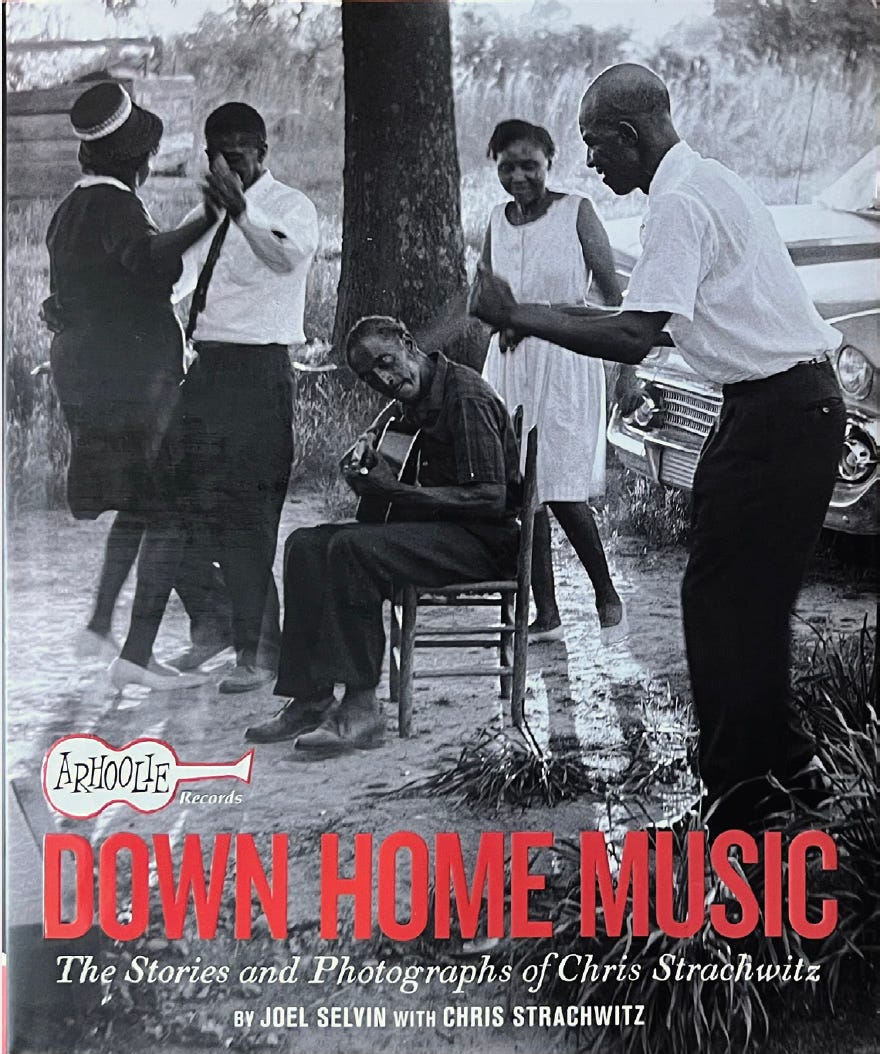

Newly published book of six decades of Chris Strachwitz stories and photos about American vernacular music — blues, gospel, Cajun, zydeco, bluegrass, Texas-Mexican Norteño, and more.

By Jim Hance

The history of the phonograph record only goes back about 100 years, but it marked the beginning of historical records for music of all types, and was particularly important for exposing and celebrating genres of music that had previously only been performed in people’s homes in rural communities. This “down home music” or “roots music” was mostly unknown outside those communities. The advent of the first standard record format known as “the 78” in the late 1920s and the mass production of phonograph players and records made roots music accessible and shareable among the general public for the first time.

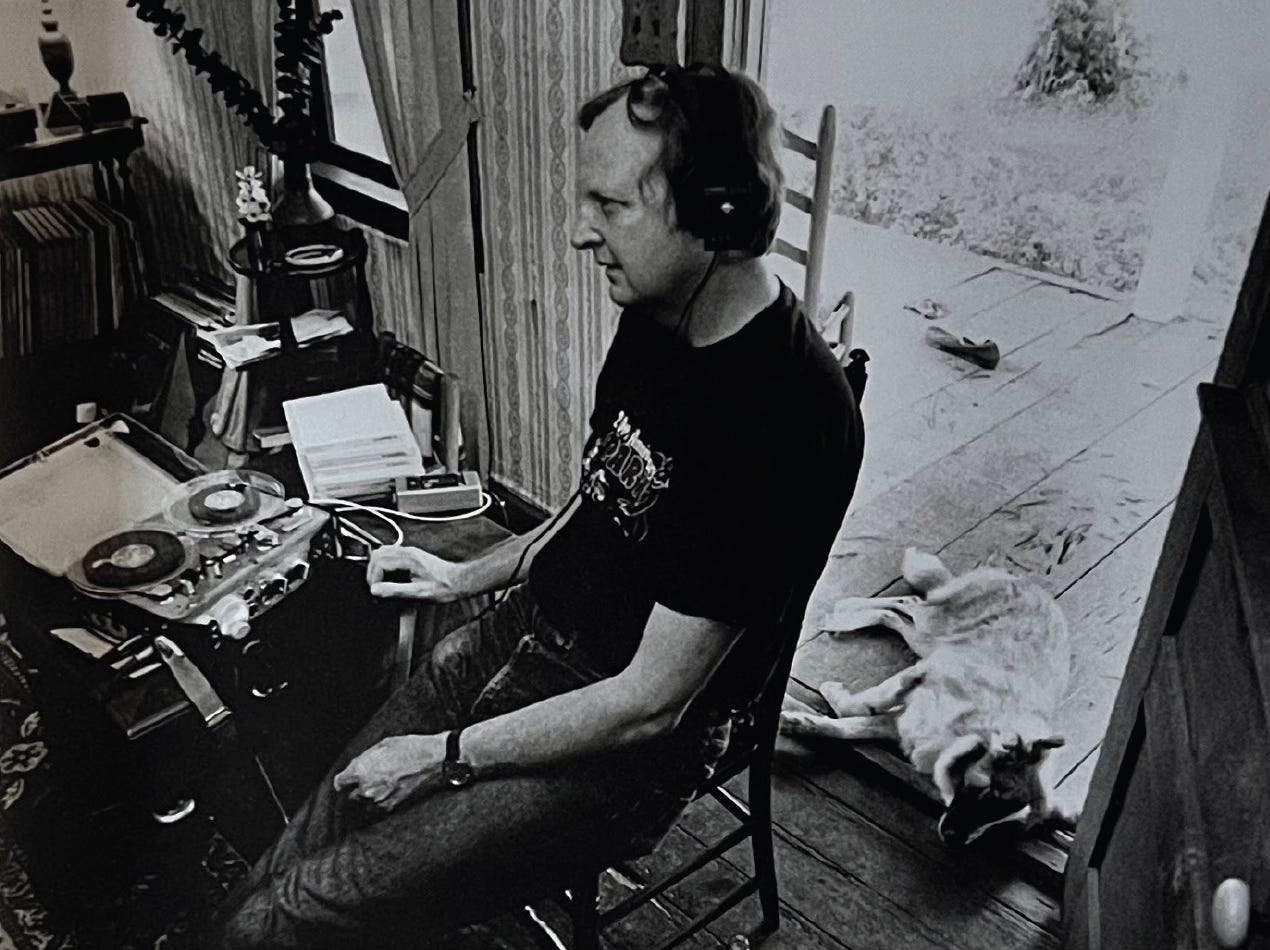

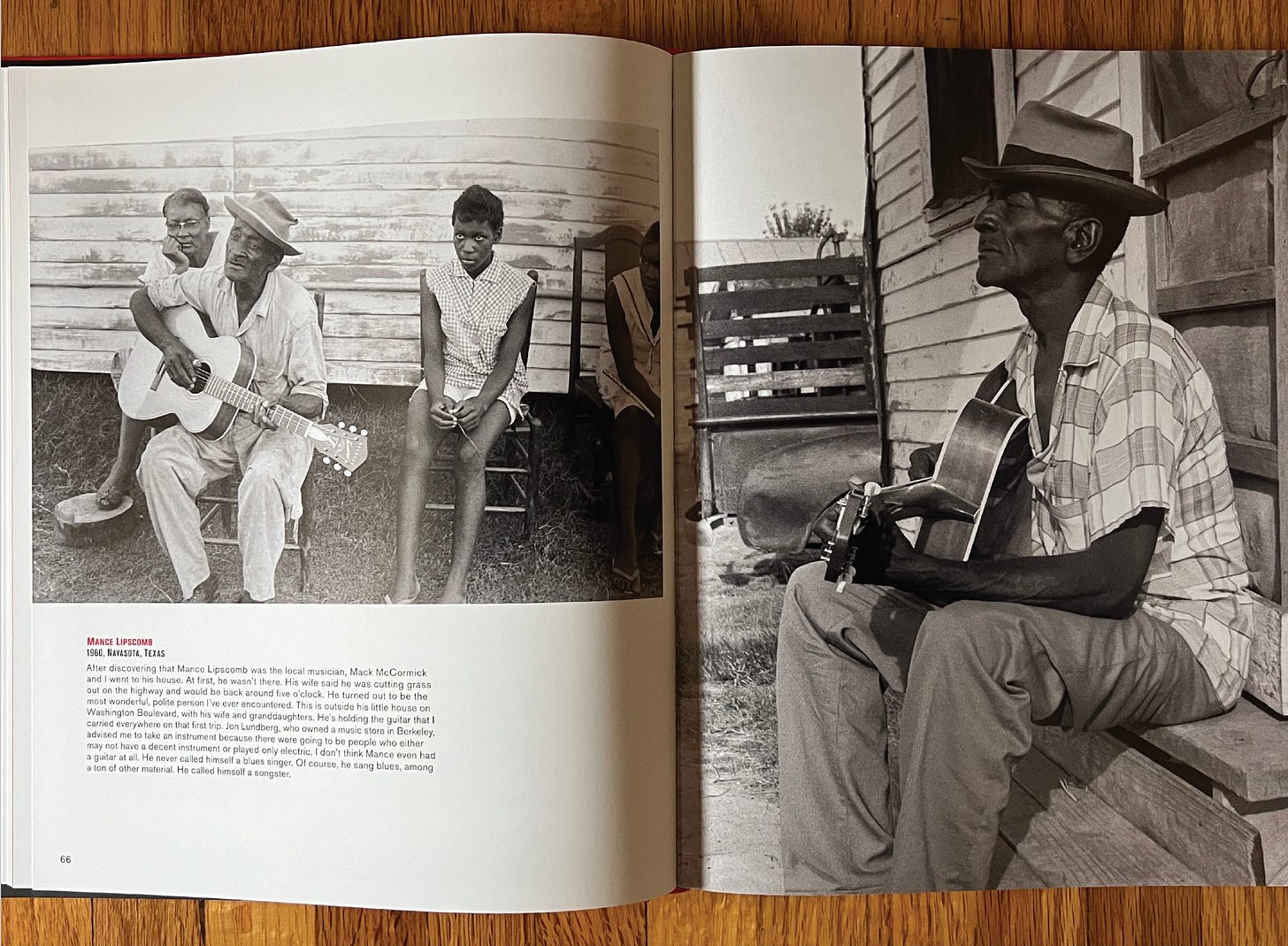

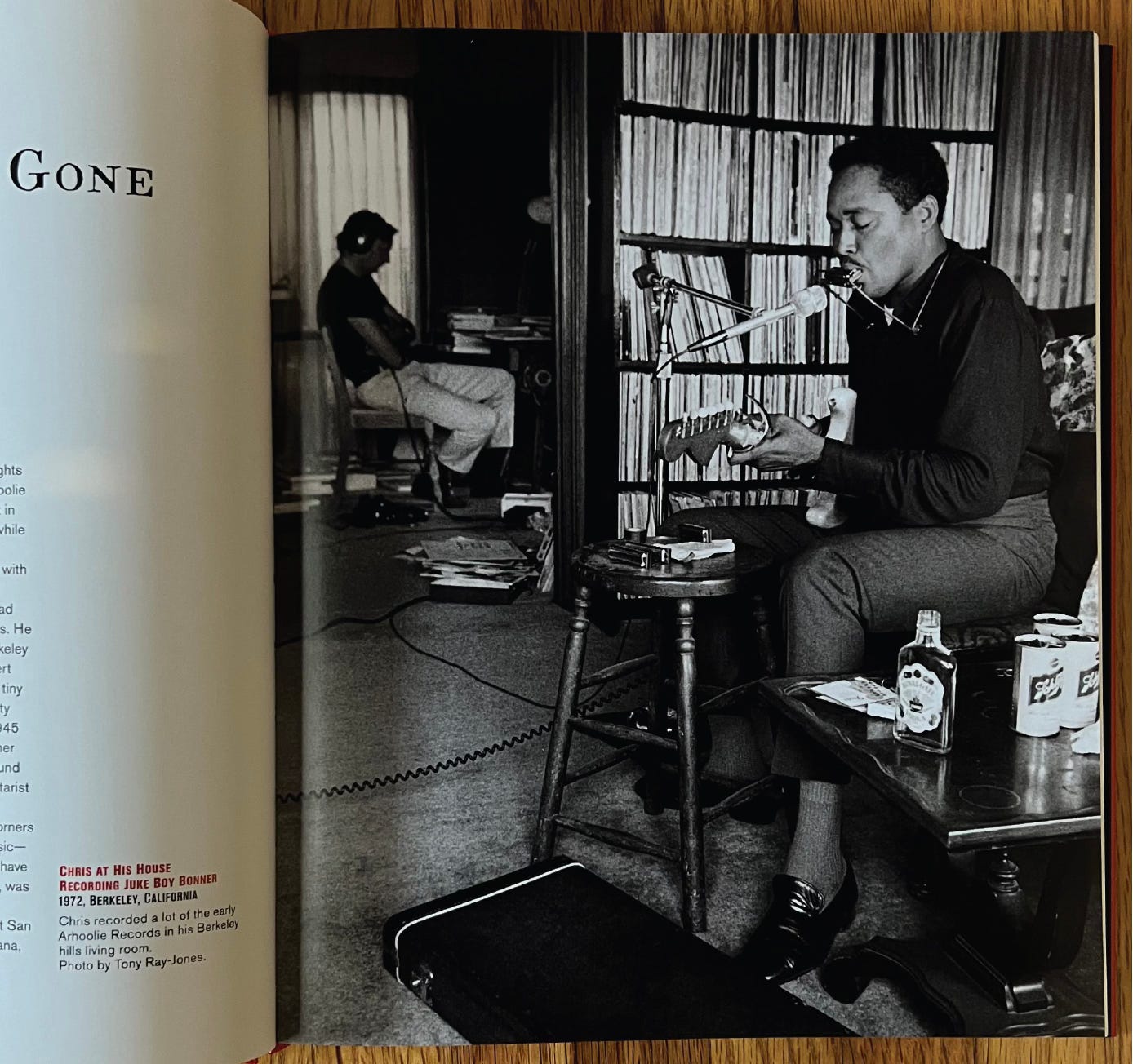

The invention of the 78, and later in 1948 the Long Play 331/3 R.P.M. “LP,” would preserve the recorded history of music that made it into the recording studio, but that’s where the stories of Chris Strachwitz picks up in Down Home Music, a book released in November 2023 with the stories and photos from Arhoolie Records owner Chris Strachwitz. Someone needed to pursue those roots music artists, interview them, learn their stories, take their pictures and get them recorded.

A young man named Chris Strachwitz, who had immigrated to the United States from Germany at the age of 16, learned about American jazz and blues music from movies and listening to the radio. While attending Pomona College in Southern California, he schooled himself in the rich variety of American music on the margins of society — country, jazz, gospel and blues. He first heard Texas bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins on Hunter Hancock’s “Harlem Matinee” on Los Angeles radio, and he was enraptured by the singer’s grizzled, ageless voice. Hopkins became his favorite blues singer and a touchstone for everything that would follow.

Strachwitz was 28 years old, and teaching German in a public school in Los Gatos, a small town an hour’s drive south of San Francisco, when he received a postcard from fellow blues scholar Sam Charters in Berkeley that he had located Lightnin’ Hopkins in Houston. As soon as the summer break came, Strachwitz headed to Texas to see the bluesman.

According to the author/editor of Down Home Music, Joel Selvin, “That rainy night in Houston, on a trip he would later describe as ‘a prilgrimage,’ where Chris first heard Lightnin’ in a low-rent Third Ward beer joint called Pop’s Place, the legendary bluesman ad-libbed his way through a recitation of the evenings difficulties — bad weather, car trouble on the way to the club, aches in his joints — winding up by noting, ‘And this man come all the way from California just to hear po’ Lightnin’ play.’ This was Strachwitz’ road-to-Damascus moment. His life would never be the same.

“For the next thirty years or so, Strachwitz would document his travels with a tape recorder and a camera. As he assembled his vast library of field and studio recordings of indigenous American musicians, he collected a reservoir of photographs along the way that unwittingly chronicled his deep journey into the heart of American music. It all began with his fascination with Lightin’ Hopkins.”

The following year in 1960, Strachwitz released his first recording for his new record label, Arhoolie Records. The record company, run entirely by Strachwitz, would eventually release more than 400 records by many artists representing many different genres of roots music including blues, gospel, Cajun, zydeco, bluegrass, Texas-Mexican norteño music, among others. Strachwitz was quite timely in coming on the scene when he did as many of the pioneers of recorded music 30 years before were still alive. Strachwitz was able to capture many of them on tape and publish them on Arhoolie Records even though some had retired or not pursued music as a profession.

The stories portion of the book recounts most of the recording trips and projects that Chris Strachwitz made over the years, as though they came straight out of a diary. But Joel Selvin has cleaned it up, filled in details of the times, and put everything in the third person, making it an easy read. An example of this is Selvin’s description of Berkeley, California: “The Berkeley he moved into was a burbling cauldron of musical, social and political changes. The University of California campus dominated the landscape, and new ideas and new attitudes were part of Berkeley life, the early rumblings of the coming counterculture. Poets and folk singers could sometimes be heard at the Blind Lemon, a San Pablo Avenue beatnik bar. The Jabberwock on Telegraph Avenue featured a steady stream of folk music; guitarist John Fahey was a regular. Strachwitz preferred the Cabale on San Pablo Avenue, where the musical fare ran more toward the down home sound he craved.”

Here is the story of how Strachwitz met Clifton Chenier. “Strachwitz spent his time hanging out with Lightnin’, who took Strachwitz in his Cadillac to see his ‘cousin’ Clifton Chenier. Strachwitz knew Chenier from the rock’n’roll-flavored 45s Chenier did for the Specialty label in the ’50s and was not especially enthusiastic at the prospect. They showed up at some tiny beer joint with a low ceiling in Frenchtown on the southeast side of town, where Strachwitz laid his eyes on this scrawny Black man wearing a giant piano accordion, backed only by a drummer bashing away, Chenier wailing away on vocals in some strange French patois that strachwitz could not understand. He was blown away. He had never heard such sounds.”

After a decade of recording obscure blues artists, Strachwitz discovered Tex-Mex music. “For Strachwitz, it was the blues all over again. No Anglos whatsoever were interested in this music, and the few Latino scholars who studied the music concentrated on the more literary ballad forms. Norteño music was poor people’s music, and nobody cared about it but the people who made it and the people who listened to it. The history of the music was not readily available. The old records were difficult to find. The musicians were aging. He felt like he had stepped into a parallel universe.

“For ten years, he had plumbed the blues world and the rewards were diminishing. He had scoured the South for any remaining vernacular musicians he could find. He came late to the Chicago blues scene, which had practically dried up and blown away by the time Strachwitz started mining there. He had made every kind of blues record, some many times, and the new blues musicians were all white, devoid of the cultural associations that made the music so attractive to Strachwitz. To him, blues was never a musical idiom; it was a way of life. And just as intriguing as the life of Lightnin’ Hopkins was to him, now these Texas-Mexican musicians with their accordions and bajo sextos captivated Strachwitz.”

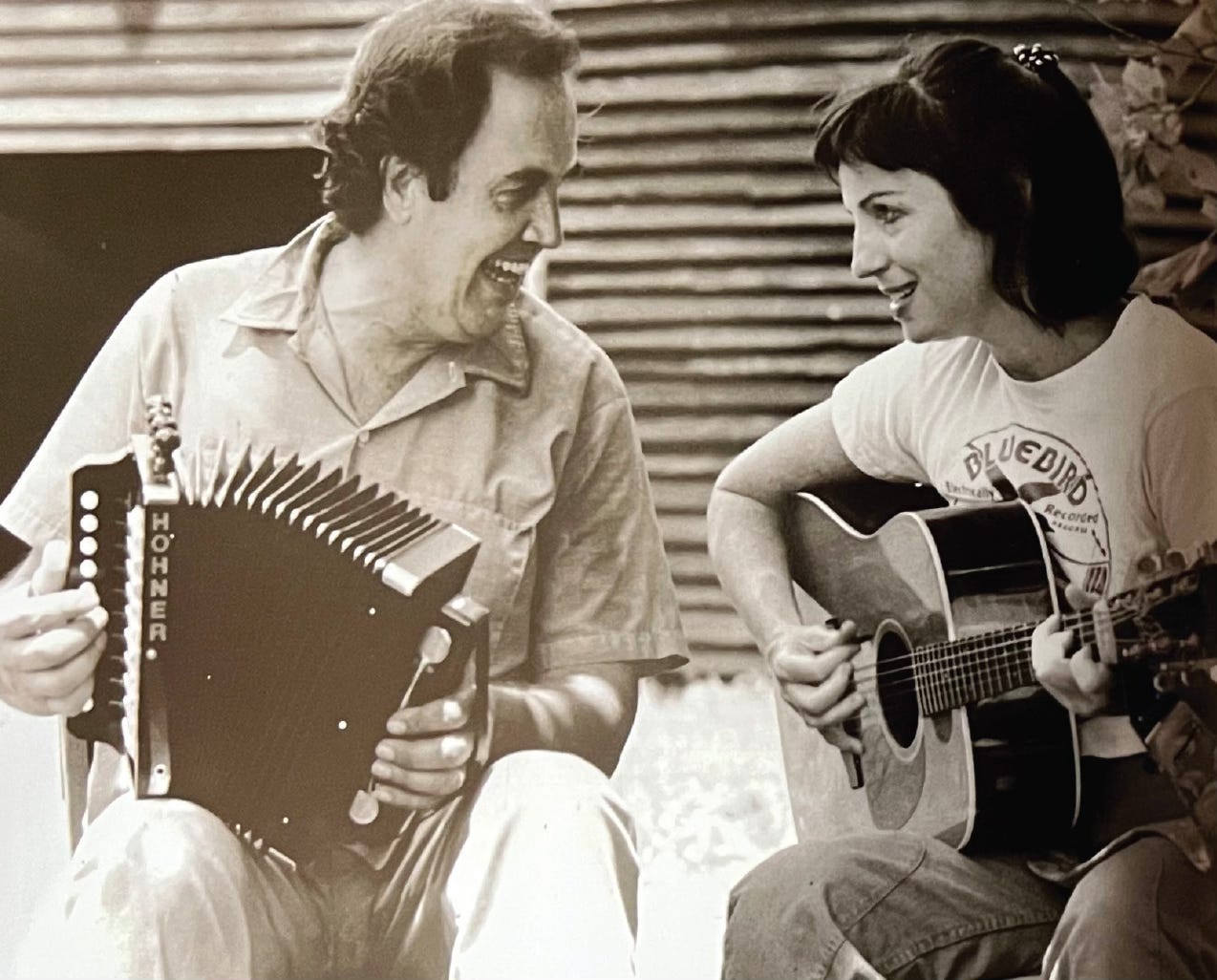

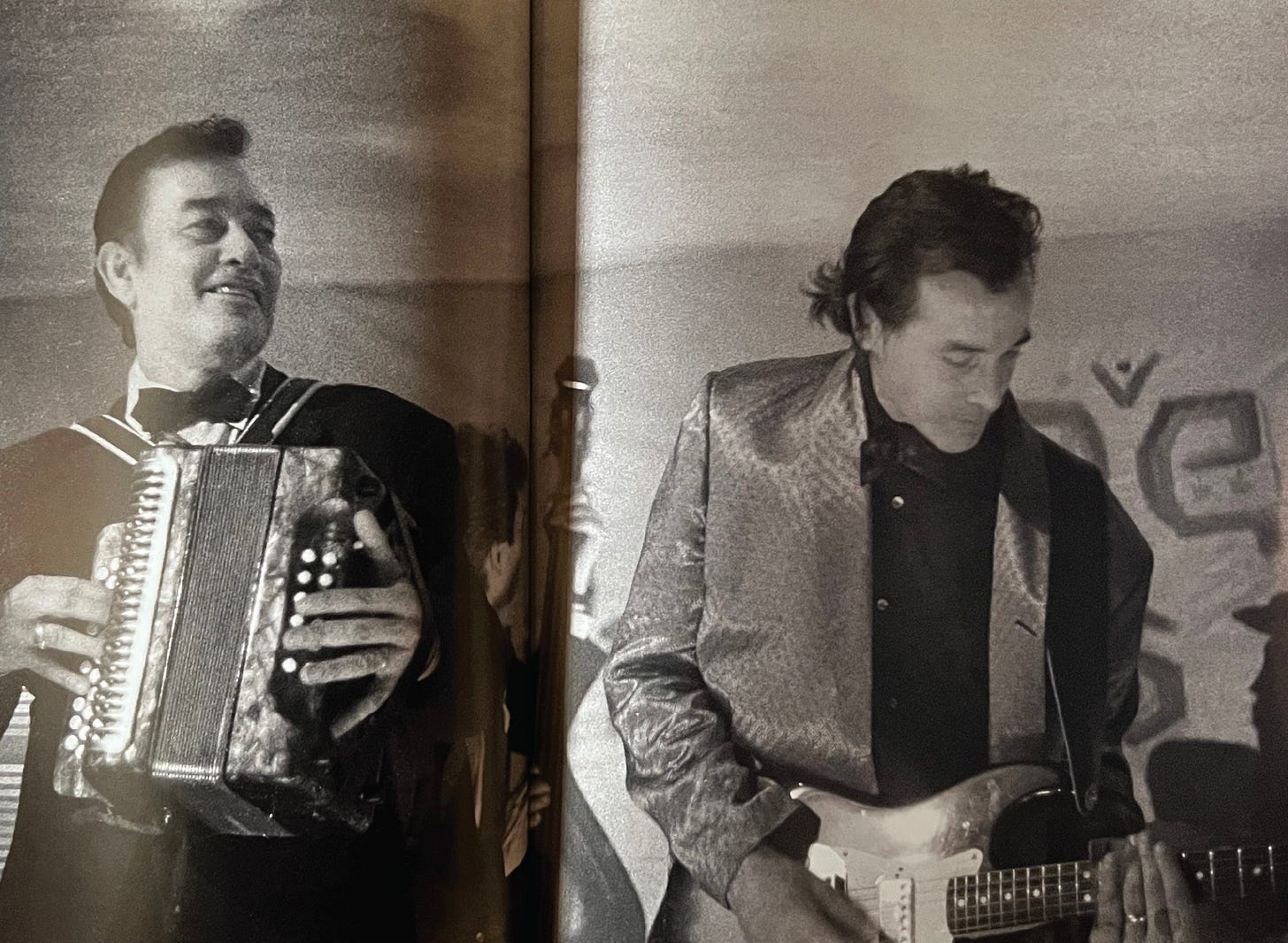

In this description of a trip to New Orleans JazzFest in 1980, Strachwitz records Marc Savoy and meets Ann Savoy and Michael Doucet for the first time: “The next week, after the second Jazzfest weekend, Strachwitz started recording with Marc Savoy at Savoy’s Eunice home. The first sessions involved accordionist Moise Robin, a veteran of ’30s 78s with fiddler Leo Soileau, along with D.L. Menard on guitar and Michael Doucet on fiddle. Strachwitz did not yet realize the significance of his meeting Doucet, a young musician who had studied at the feet of the Cajun masters, but he would soon learn. A couple of days later, twenty-nine-year-old Doucet returned to sing and play guitar on the first solo album by Marc Savoy, a loose, informal session that prominently featured vocals by a cousin named Frank Savoy, a funky backwoods character from Church Point who lived behind a beer join. Also helping out on guitar and vocals was Marc’s wife of three years, Ann Savoy, who would become her husband’s closest musical collaborator.

“Twenty-five-year-old photographer Ann Allen of Richmond, Virginia, had met Michael Doucet, who was playing with his Cajun rock band Coteau, and Marc Savoy, who was hanging out and jamming with Dewey Balfa and others at the National Folk Festival at Wolf Trap, Virginia, in 1976. She fell in love not only with the burly Cajun accordion maker but the entire Cajun culture. Within a year, she had moved to Louisiana, married Savoy, and begun studying Cajun history and culture for a book. A French student, she quickly learned to sing in Acadian and became an integral musical partner to her new husband.”

Ry Cooder, a recording artist famous for collaborations with other musicians of many different traditions and countries, recounted: “I traveled through South Texas with Chris for a few days once. He had his tape machine, a change of clothes, and a twenty-five-pound sack of oranges. Texas is big, you know. Five hundred miles a day — he stopped to eat only to be polite. He wore me out, but I learned a lot. The border Mexicans called him “El Fanático.” Chris is a really nice man — he liked the musicians, they liked him back. Even Mario Montes, the accordion player of Los Donneños, who had no use for white people, put up with him. Then, it was drink your orange juice, get in the car, and drive. Viva El Fanático!”

An unlikely testimonial for this book comes from Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top: “Chris Strachwitz is a heroic figure if ever there was. This book gets to the root of roots music and tells the story of Arhoolie most brilliantly.”

Bonnie Raitt wraps this review up: “No one has meant more to the preservation and appreciation of Americana roots music than Chris Strachwitz. He turned me on to Mississippi Fred McDowell and so many other greats. With his passion for the artists as people as well as their culture, and the creation of Arhoolie Records and Down Home Music, he’s given us some of the most thrilling and unique music we’ll ever know. How great that Chris and Joel have collaborated on telling his fascinating story in this wonderful book.”

IN THE SPOTLIGHT :

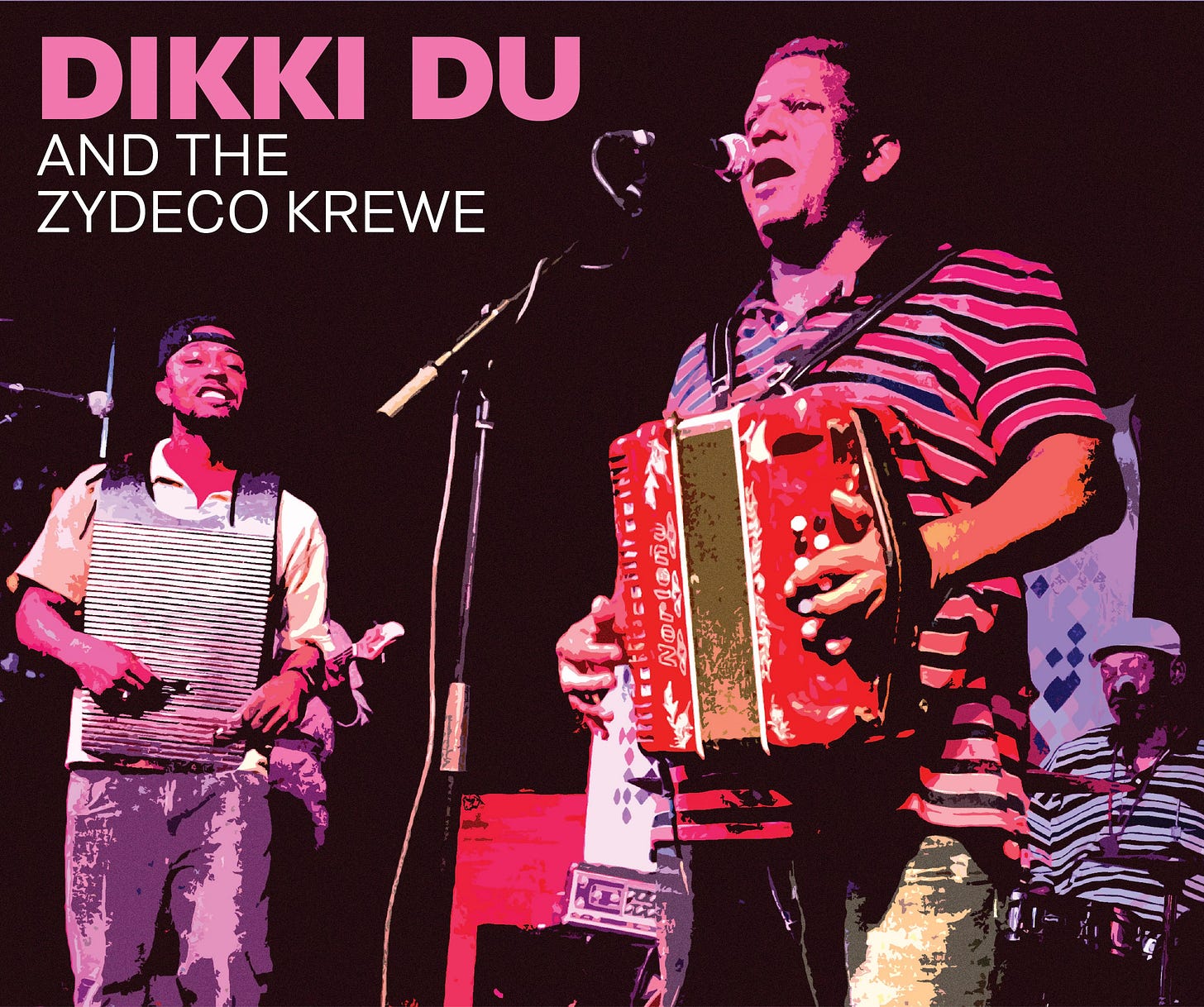

Dikki Du: It’s All in the Family

By Jim Hance

Dikki Du (Troy Carrier) was born in 1969 in Church Point, Louisiana into one of the premiere musical families of zydeco, the Carriers. Dikki Du was a nickname given to Troy by his godmother for his stinky diapers as a baby. After school he would get together with his brother Chubby, sister Elaine and father Roy to play zydeco music. His musical idol growing up was his grandfather, John Carrier, and since childhood zydeco has been the only kind of music for Troy.

At the age of 9, Troy was incorporated into his dad’s band, Roy Carrier and the Night Rockers, playing washboard and performing often at Roy’s nightclub, the Offshore Lounge in Lawtell. Chubby Carrier was in the band as well on drums. Roy Carrier’s main occupation was working the offshore oil rigs which he did until the late 1980s. A couple years after forming the band, Roy moved his family to Lawtell.

Roy Carrier was a huge fan of Clifton Chenier’s style of zydeco and blues, and when the Night Rockers band was starting out about 1980, Chenier, who promoted himself as the King of Zydeco, was the most popular zydeco artist in Louisiana. Clifton Chenier created zydeco by combining various genres of music that existed side by side in Louisiana during the 50s. Zydeco had been mainly a rural music, played at house parties and cookouts with just accordion and washboard. It was sung in Creole French, and called “French La La”. It then moved to the church, eventually becoming entertainment for Saturday night socials. Clifton popularized it for the stage in 1955 by combining blues and R&B with Cajun dance music made up mostly of waltzes and two-steps. This melding of diverse musical styles and instrumentation made zydeco an exotic and exciting form of American musical expression.

Even today, Troy favors the “traditional” zydeco sound with a heavy blues influence that Chenier played and that he heard being played in his home rather than R&B and pop influenced contemporary zydeco.

After a few years, Troy joined C.J. Chenier’s band for two years, while Chubby toured as a member of Terrance Simien and and the Mallet Playboys. Roy Carrier replaced his sons in the Night Rockers with Phillip Perrodin on rubboard and Calvin Sams on drums, and the band went on to be named The Best Zydeco Band several years running in the late 1990s by Real Blues Magazine.

Chubby started a family band and offered Troy a job playing the drums. In the 1990s, Troy focused on learning to play the accordion and In 1997 he formed his own band, Dikki Du and the Zydeco Krewe. Since then, Dikki Du has incorporated his musical heritage still influenced by John Carrier and Clifton Chenier, and played with a little faster tempo than most contemporary zydeco with some of his own funky and hypnotic styling added.

“Personally the triple row accordion is the sound that I like the best,” says Dikki Du. Joining him in the Zydeco Krewe are Troy’s aunt, Laura Dolittle, on washboard, Greg Gardner on drums, Burnell Babineaux on bass, and Jill Gilbert on keyboard.

According to one reviewer, “What a sound! Dikki and the Krewe stretch out songs and it is great to dance to, as well as to listen to. Hard driving and relentless is the theme all night. It’s just funky as can be. Nice polyrhythmic grooves going around the stage, and on the dance floor. Dikki Du and his krewe come out ‘smokin’ harder and faster in the second set.”

One Dikki Du fan in California commented, “When I was in Lafayette with my girlfriends, we would search for where Dikki Du was playing. We loved his beat and charge. He is the closest in style to Geno Delafose."

Dikki Du’s only album to date of music on iTunes is Straighten It Out, released in 2006. But the good news is that he will be releasing a new album in 2024 to be titled Louisiana.